Mermaids vs. Vampires

Why would a woman want her life’s blood drained away to spend eternity with a dead man? Not my idea of romance. Mermaids offer more hope.

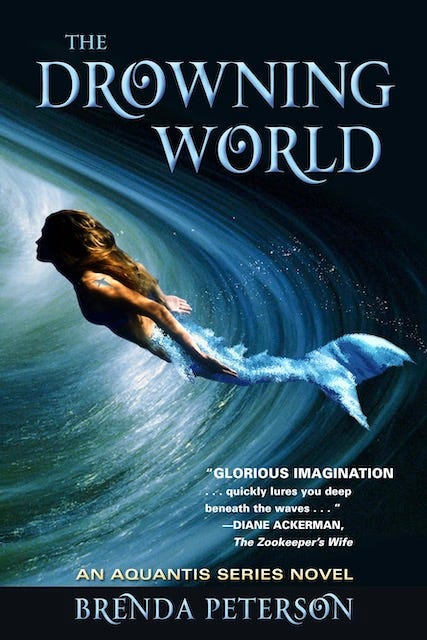

Disney’s blockbuster re-release of “The Little Mermaid,” and the million-dollar mermaid industry in its wake, makes me wonder: Why are mermaids edging out vampires in our pop culture, especially for young women? When I began my mermaid series, The Drowning World, in 2010, there were few tail flukes in current film or fiction. A New York editor told me, “Mermaids are ancient history. Vampires are what’s hot.”

It’s not that I didn’t like vampires; it’s just that I don’t get why a woman would want her life’s blood drained away to spend eternity with a dead man. Not my idea of romance. So, I just kept writing about mermaids. Creating a cosmos takes time. The Drowning World, my novel of shape-shifters surviving Flood Lands and climate change, was published in 2012 — right before Hurricane Sandy flooded the East Coast. Since then pop culture and our coastlines have also undergone a sea change.

“Are Mermaids the New Vampires?” Digital Journal asks. Mermaid books, especially YA crossovers, were suddenly so ubiquitous that one of my editors protested, “Some of them are even vampire-mermaids. Cheesh!”

What happened? Why was Animal Planet’s 2012 “Mermaids: The Body Found” one of their biggest ratings hit — a “mockumentary” that prompted NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) to issue a disclaimer that “mermaids are not real.” Netflix has a popular new 2023 reality series, “MerPeople” about professional mermaids; and NPR’s Marketplace reports that the million-dollar industry of “mermaiding” is a tidal wave of profits. Many of us, now even men, want to be under the sea, with our gorgeous and expensive tails.

“The weight of the world can be so intense . . . this is an escape from all of that,” says a mermaid in the Netflix series. So, who not dive into our blue planet’s buoyant, weightless world?

But maybe mermaid stories and wanna-bes are much more than escapist myth. Climate change may be unconsciously driving some of these mermaid stories, especially for younger generations. We always tell tales about how to survive. In a future of rising seas, will we actually learn to be more amphibious? Will we someday have to leave land and live in floating cities or undersea? Better get a set of life-saving tailflukes.

Having spent the last decade creating merpeople of my own; and having also spent three decades underwater studying whales and dolphins for my nature books, I have some ideas why vampires are ebbing. Whenever one myth replaces another, it’s fascinating to understand why.

Here’s a quick comparison of vampires and mermaids in mythology:

VAMPIRES

1. Die to become undead

2. Feed off humans

3. Addicted to human blood

4. Compel humans

5. Powerful and sexy

6. Stylish and immortal

7. Make love and war

8. Secretive, taboo, mysterious

9. Plot: A Stranger Comes to Town

10. Romance of The Other

MERMAIDS

1. Shape shift between worlds

2. Fall in love with humans

3. Don’t need humans to survive

4. Mesmerize humans with songs

5. Powerful and sexy

6. Stylish, but mortal like humans

7. Make love more than war

8. Secretive, taboo, mysterious

9. Plot: A Stranger Comes to Town

10. Romance of The Other

Mermaids practice more feminine power than most vampires. Like many female wild animals, mermaids choose their own mates. So mermaids are action heroes in their own rights; they are not just acted upon by dashing male vampires who recreate women in their undead image.

So many of us, now even men, want to be under the sea.

Unlike the tragic, self-destructive Little Mermaid of Hans Christian Anderson’s classic tale, our 21st century mermaids in books and film can live between sea and earth with style and pleasure. And unlike the vampire stories, in which death or war are the main themes, mermaid myths focus most on romance and struggling to fit in — or not.

For girls and women, adapting to our ever-changing roles and societal expectations, our focus on relationships is like shape-shifting. We are always in moral and romantic dilemmas, such as: How much do we change ourselves to be loved? In a global village, can we love The Other/The Outsider/The Forbidden?

When popular culture and the stories we tell ourselves shift from vampires to mermaids, it suggests a more regenerative and hopeful trend. We seem more concerned with the living and our own survival. We don’t long so much for death or the apocalyptic end of the world. Mermaids rising up with our seas beckon us to pay attention to their siren calls, to dive into our own depths, to fully fathom the oceanic womb that first, and always, gives our species life support.

Vampire stories haven’t cared much about saving our human world and habitat. But many real mermaids are activists. Professional mermaids, like movie star-mermaid, Hannah Fraser, swim with wild dolphins and whales to raise awareness of the danger — like military sonar — destroying our seas. Megan Heaney-Grier, a U.S. Free Dive champion, whose mermaid photo graces the cover of The Drowning World, also champions’ shark conservation. Then there is “Mission of Mermaids,” an elegant ocean conservation movement.

Mermaids don’t fall in love with eternal death. They fall in love with flawed and complicated real life, specifically humans. Mermaids, unlike vampires, want to stay in this world with us. They long for us, for our land and our legs. But they also have their own alternate universes that are complex and multi-dimensional. Mermaids have much to teach us about surviving a drowning earth. To mermaids, ours is not a dying world, but one worth loving — and saving.~

Bio:Brenda Peterson is a novelist and nature writer, author of more than 20 books. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, Seattle Times, and Oprah magazine. Her mermaid series, The Drowning World and Tattoo Master, are in paperback and will be out in audio this summer. Her new mystery novel, Stiletto, is just out. The book launch is June 8th, 2023 7 p.m. at Elliot Bay Books. www.BrendaPetersonBooks.com