Wolf Eyes

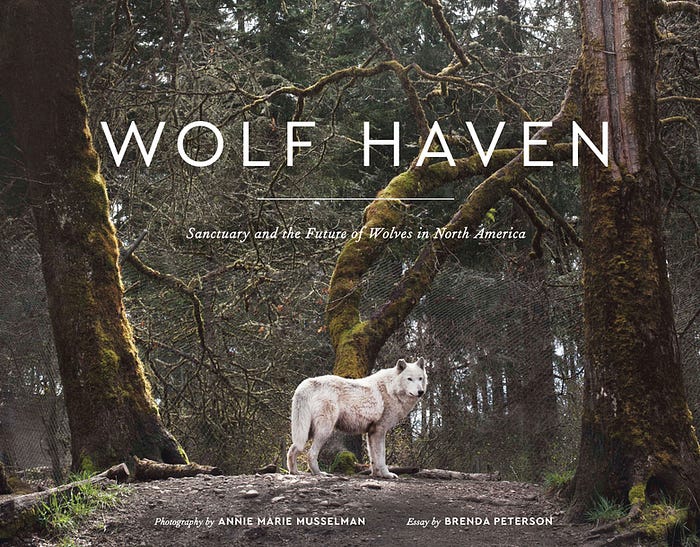

Excerpted from the book “Wolf Haven: Sanctuary and the Future of Wolves in North America,” essays by Brenda Peterson, all photographs by Annie Marie Musselman. (Sasquatch Books)

THEIR EYES FIND you first, often golden or dark-green and amber-flecked with a fierce and surprising intimacy. Direct, intelligent, eerily familiar. Though these wolves in their refuge at Wolf Haven are no longer wild, there is nothing tame in their gaze. Instead, there is a rich and vivid emotional life that we can somehow read, not just because humans have lived closely with Canis lupus since prehistory, but also because the wolves mirror us. And even behind fences, they connect. First contact.

One white wolf’s stare is stunning — Bart commands our complete attention, even as he rests, with his lean legs almost casually crossed. Lonnie’s eyes are shy but steady as he peeks out from behind branches. His expression reminds us that in the wild, wolves are extremely wary of humans and spend most of their lives hiding from us. Delicate Lexi, with her flattened agouti-colored ears, looks back cautiously at us as she retreats. Tala, the slender red wolf, steps so lightly and silently out of his hiding place that he startles us. Lowering his sleek mahogany head, he gives us a quick searching glance — and then disappears.

Even the abandoned wolf dogs — those who, as Wolf Haven’s director of animal care, Wendy Spencer, says, are “caught between two worlds” — haven’t lost the wildness or expressive depth in their eyes. Caedus, the lustrous black male wolf dog who shares his life with the delicate and somehow sad-eyed Ladyhawk, stands sentry, his buttery eyes both bold and curious. He might as well be perched protectively atop a remote mountaintop, scanning for his pups and family.

How many of us have actually ever had the privilege of looking into the eyes of a wolf? How many of us would ever know if a wolf was secretly watching us in the wild? We couldn’t smell them the way wolves can scent humans from half a mile away. We couldn’t hear them, unless they howled. Sight is the only way we sense a wolf, so they are at the advantage when it comes to sensory gifts. And even then, the wolf’s unblinking and powerful gaze is unusual in our species. Perhaps that’s why we stand riveted at the fence or in the forest when we catch a glimpse of this fellow creature.

“Wolves look right through you, don’t they?”

That’s what a Yellowstone biologist told me in 1995, as we watched the first reintroduced wolves in America. The Soda Butte family scampered with their pups and loped across a high meadow. Even from half a mile away, the wolves were keenly aware of our presence.

“Yes, they do,” I breathed, barely able to hold the telescope, my hands were trembling so.

Yes, I still feel that intense energy running between wolves and humans every time I visit Wolf Haven and encounter these animals who have found a retreat here since it opened in 1982 — giving sanctuary to more than 200 gray and red wolves, plus wolf dogs and even coyotes. We recognize ourselves in wolves — our own hungers, passions, violence and tenderness. Anyone who spends time with wolves understands that their social dramas — who’s in, who’s out, who’s on top, who’s struggling to survive, who’s ailing or lost, who is thriving — are as fascinating as our own. In the wild, wolves live in close-knit and complicated families. They are affectionate and loyal to their young, and the whole group cooperates to survive together. At Wolf Haven, these often-abandoned, -abused, -mistreated and -misunderstood wolves are given another chance, not only at living, but also at bonding with one another.

A lone wolf is a rare wolf.

All you have to do is hear a wolf howl to intuitively know that wolves always seek community. Just like their profound eye contact, the wolf’s howl is a language of loss and longing — and sometimes even joy — that we also instinctively understand. As you enter this book of Canis lupus portraits and stories, remember that you are in the presence of an animal who has always belonged very near us. Another top predator who has inspired in us both passionate devotion and unjustified cruelty. Another animal who even in a shelter is very much our equal: a spirit who can still hold and meet our eyes.

— Brenda Peterson

NOTE: The Trump administration delisted wolves from federal protection throughout the country and WA state wildlife managers will kill an entire pack, 12% of the entire state wolf population. Check out Center for Biological Diversity and Wolf Haven International to help wolves thrive.

From the photographer: Annie Marie Musselman:

“HOW CAN I photograph anything from behind a fence?” I wondered, given the restriction at Wolf Haven International that my subjects would be on one side of the barrier and me on the other.

Still, I was eager to start shooting, and despite a storm warning, I drove the 75 miles from Seattle to Tenino in tense, slushy traffic. Then I arrived at a kind of forested wonderland complete with jet-black ravens circling above. I pinched myself. Dream or reality? Mature trees blanketed by moss towered overhead; a vast prairie bordering the sanctuary was alive with pocket gophers, bald eagles, hawks and an array of lush flora and fauna. Everything seemed to glitter, although it was dark and cold at noon, no sun in sight. All I heard were ravens chortling and the wind whispering in the trees. Wendy Spencer stood next to me — a kindred spirit, for sure — giving me the lay of the land and describing my boundaries, and how to act around these timid-fierce creatures.

Then I saw the wolves.

They appeared softly from behind trees and branches, looking intensely at me, taking me in. Wolves are difficult subjects for a photographer because they truly hate having their pictures taken, or even to be stared at, for that matter. So I had to prove that I wasn’t a threat, and this took precious time.

I portrayed the wolves as if I had met them in a natural forest. Sometimes I showed the fence to present the truth of their lives there. The land at Wolf Haven comes as close to the environment of their births as possible. The wildness of their surroundings that had been stolen has been returned in the gift of true sanctuary.

In the summer, I spent long days with Jesse James, a female gray wolf, and her partner, Shiloh. I sat on my dad’s old folding artist chair, surrounded by moss trees with birds and insects buzzing around and the sun glinting through. I pretended not to be interested in them at first, but as soon as I walked away, I turned around and there both of them were at the fence, smelling and staring at me. They want me to come back? When I did, they would disappear again. This went on for weeks or more, until finally they began to trust me.

In the quiet of the forest, I watched their beautiful friendship unfold before me. Jesse would appear, then disappear behind trees, then appear again right in front of me, unaware, striking and powerful. And then she was with me. An ancient being within reach. Behind us both was our history, our loving mothers, our families and the homes and forests where we grew and that we both missed dearly.

I sat with them for hours to uncover a moment of connection between two beings. I often used lighting to show the hidden intricacies of their beauty: the dirt on their fur, their sharp teeth and their arresting eyes that can often be hidden by shadows. At first I was afraid of their ferocity and their unsettling stillness. I also feared not being able to capture their exquisiteness on film, but slowly I began to take them in and to envision their existence. I thought of their need for connection to one another; incredible sense of smell and eyesight; their heightened awareness of everything encircling them; and their ability to remain calm, most of the time, through it all.

We connected through our eyes and, I believe, our hearts. How much I will miss you, sweet Jesse and Shiloh. Jesse passed away from complications of old age this past year, within days of Shiloh’s sudden death. They were truly in love.

Driving back to town, where lives rush by and begin and end, I thought about the wolves and the silence in the sanctuary. I saw the sun piercing through their fur as it glowed and could feel myself sitting quietly in nature, paws crushing through the grass.

Animals connect me to my true self. I ache to have a second of their exquisiteness. There is an inner quiet and peace that can be found only while lost in the woods and meeting a gaze with a wolf or a raven or an owl. A wonderful dream. I tried to manifest that feeling in these pictures.

I photographed through small holes in an incredibly strong fence that protected me. But it couldn’t keep me from falling deeply in love with these highly intelligent, beautiful beings.

— Annie Marie Musselman

Learn more about Brenda Peterson’s work at BrendaPetersonBooks.com. Learn more about Annie Marie Musselman’s photography at AnnieMusselman.com.

• Brenda Peterson is a National Georgrahic author, memoirist, and novelist. Her 20 books celebrate animals and nature. Since 1993, she has covered wolf issues for national media. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, ORION, Oprah, and on NPR.

• Annie Marie Musselman’s first book, “Finding Trust,” was published in 2013. Her work has been published including Smithsonian, Audubon, Outside, New York Times, and National Geographic.